|

|

Japanese soldiers passed through the town of khun yuam on their retreat from Burma, and in their wake are traces of the friendship and humanity that flourish even in war.

Nations use many methods to look after and safeguard their interests.but when everything else fails.they turn to war.

The means of waging this final resort encompass both the mechanical-weapons-and- the human-the soldiers who wield them.Soldiers' brains have been imprinted with a sense of duty that tells then they must fight for their homeland.

From the time they begin wearing their uniforms and carrying their weapons, they know they may have to die. They must continue ahead with this thought in mind until the war reaches its conclusion with a victorious nation and a defeated one.

But while the conflict it still raging, a soldier has no way of knowing whether he himself will be a winner or a loser. On one day he may be planting a flag on newly-captured territory, and then the next day he may stop a bullet, or lay shivering and panting with fever.

Just such a reversal took place in the fortunes of the Japanese during world war two. During the time they occupied Thailand, they seemed invincible, and it was then, in 1941, that they constructed the "Death Railroad" that crossed the Khwae River into Burma

The railroad attained global notoriety because of the great number of Allied prisoners of war who died constructing it. The body count almost equaled the number of wooden ties supporting the tracks over the rail-road's more than 400-kirometre length.

The Japanese crossed into Burma and were victorious there too. They planned to continue on into India to establish them selves as the sole power in Asia. But then, in 1944, only three years after they were at their peak, the Japanese army sustained a powerful attack in India.

The victors became the defeated as they fell to wounds inflicted by weapons of war and to jungle fevers. With-out medicine and food, they retreated, as sick and emaciated as the allies they had held prisoner.

The route they took to escape death in Burma passed through Amphoe Khun Yuam in Mae Hong Son province. All of the residents of this small town were Thai Yai. And as the sick and wounded Japanese arrived there the townspeople gave them all the assistance they could. They didn't give any thought to the question of who was or wasn't a war criminal, they treated the soldiers as fellow human beings who were seriously ill and in some cases dying. Every day they dug graves for the ones who succumbed until there was almost no space left to bury any more.

Now, surviving soldiers remember Khun Yuam by a special name they have given it: the road of Japanese skeletons.

Today there is a museum at Khun Yuam called Japanese soldiers in the memory of the inhabitants of Khun Yuam: The Second World War. Its creation was initiated by Lt Col Chiedchai Chomthawat , deputy police superintendent at the Khun Yuam police station.

"After I arrived here whenever I came across anything from the world war tow era, I kept it as a souvenir he explained. "But then something else from that era started coming to me: stories about the Japanese soldiers who had arrived here.

"When I spoke to villagers 60 years old or more, they told me stories that were very exciting.

"Once an old Japanese man with a leg missing came to Wat Muay Taw, A Yhai Yai temple in the middle of Amphoe Khun Yuam. He came to war-ship at the temple, and once we had gotten to know each other he told me that he had been a soldier. and had arrived at the town badly wounded. He told me that the reason he went to worship at Wat Muay Taw was that at the time he came out of Burma after Japan was defeated in that country, there was a hospital on the site. Many of his friends had died there.

"The story of the Japanese who had come here gradually came into focus, because I was hearing about then both from the villagers and from many Japanese who came here and contributed photographs and maps. We used them to create the museum. We donated some of the money needed to set it up, and also found additional funding.

"Many of the items on display were contributed by the villagers. These include canteens, clothing, guns, and medical equipment. Right now the museum resembles a storeroom, but we think that's the best we can do right now. If we get more money in the future, we will improve it into a modern museum.

"We learned that the retreating Japanese soldiers arrived here injured and crippled and stayed in Khun Yuam for over two years. The ones who were in good health con-tinued on, taking several routes. One group made bamboo rafts and set off on the Moei River, which flows into Burma. But the Moei falls into a deep chasm, and the group who tried to travel along it fell into it and the soldiers all died.

"Others left by way of Amphoe Mae Jaen and than on to Ciang Mai and down to Bangkok. The ones who were not well stayed on here to recover. They lived in villagers' houses, and many of them looked after the children while the villagers were out in the fields. That's why some of the local people who were children then can still sing Japanese songs. When the Japanese who were here as retreating soldiers come back to visit and they meet villagers who were here in those days, they sing song together.

"The Japanese soldiers were highly disciplined. People say that there was a commander, who absolutely forbade them, under pain of death, to rape local women. This was because he was aware that they were injured and in weakened condition and didn't need to make any new enemies.

But there was one who didn't want to return to Japan as he fell in love with a local woman and settled down with her and their children. He tried to keep hidden, but afterwards. When Thai officials found out about him, he was arrested and deported. I think he died on the way back. But now the Japanese are trying to find a way for his children to go and work in Japan. Everyone in the amphoe knows who they are.

"We have been locating the coffins of the dead soldiers, and every time we have dug one up, we've found some evidence of who was inside, often a sign with a name. In these cases, we've notified the Japanese, so that proper religious rites could be performed and the remains sent to Japan.

"These days there are always Japanese visiting Khun Yuam. Many of them contribute money for the education of local children. We think this is because they still remember what happened here and want to thank the people here for their compassion."

Visitors who go to the museum are likely to encounter one local man who sits in from of it and guards it. He is always ready to share stories about the past in Khun Yuam.

His name is Jariya Upara. And he explained that at the end of World War Two, Amphoe Khun Yuam was very small and all of its inhabitants were of the Thai Yai ethnic group.

"When people went to Chiang Mai to buy what they needed, it took six full days to make the trip," he related. "If they took a donkey or cow to help carry their purchases, it took half a month, because the animals would only travel in the morning before the sun was hot. In the afternoon, they had to stop.

"The route that the Japanese soldiers used to get from Burma to Khun Yuam is one that they had cut themselves. It was clear enough to travel, but only with difficulty. It was a route that had also been used to get into Burma, and had been made at the same time as the Death Railroad in Kanchanaburi.

"But it wasn't made by Allied prisoners of war. Local people were hired to construct it - Thai Yai, Karen, and others. By doing things that way, the Japanese avoided having problems with the local villagers. They didn't just build a road; they also made a temporary airport here. You can still see the remnants of it.

"I was 12 years' old then, and can remember it all clearly. The injured Japanese soldiers came out of Burma by the thousands. That was in 1944. They came on horseback, in carts, and on elephant back.

"We used Wat Muay Taw as a temporary hospital for them. A Japanese military officer named Mr. Usiyama hired me to bring him water. He would heat the water and then take off his clothes to soak in it.

"Every morning at seven this military officer would go into the temporary hospital to get a report from the doctor, then he would take some black ink and make a mark on the soles of the feet of the wounded and sick soldiers. A circle would mean that the man would recover. An X meant that he was beyond help. In these cases he gave the man a lethal injection so that he didn't have to suffer. Then he would take the dead man out and bury him. The dead were buried only about 50 centimeters deep. A wooden sign with the man's name would be placed on the grave.

"In 1978 the Japanese came here looking for graves. They were hard to locate because people had forgotten where they were. Forest fires had destroyed some of the grave markers, and other graves had caved in because many years had passed. Some men had been buried near big trees into which identifying marks had been carved. But there has been a lot of logging in Amphoe Khun Yuam, and many of those trees are gone. So most of the identifying evidence was gone.

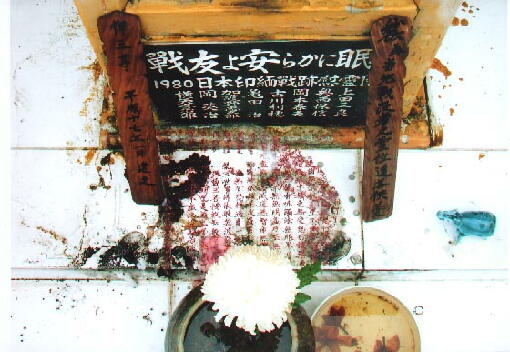

"Even so, they found the remains of more than 300 soldiers, and a group of Japanese came here to conduct a religious ceremony. Offerings were made, and there was food and alcoholic drinks. Some of the remains were cremated and sent to Japan; others were put into a single urn and buried at Wat Muay Taw. An inscribed stone marker was placed there.

"In 1989 the Japanese came back to look for more remains, and more and more have been found.

"In our amphoe there was a Japanese soldier who remained in Burma near the Thai border. He lived with a minority group who fled the Burmese military and came to stay in Thai territory. He was in a refugee camp in Amphoe Khun Yuam. He had a Karen wife and five children. The Thais called him MR Kobori, and he just died this past January. I think he was the last Japanese soldier to die in Thailand.

"I'm usually the one who keeps watch over this museum. On days when I'm not free to do it, a student who has been taught about what happened here explain it to tourists.

"What we have here are clothes, canteens, guns, and other items donated by local people. Almost every home has some of these things."

The Japanese Soldiers in the Memory of the Inhabitants of Khun Yuam: The Second World War museum testifies that although war is a cruel and brutal thing no matter where it takes place and who is involved, it also leaves behind traces that reveal friendship, Kindness, and humanity under the most difficult circumstances.

|

|

�Y�o�V��

����8�N11��10���i���j�����ł̋L��

|

�@����̃r���}�i���~�����}�[�j����ɎQ�����������{�R�������c�������e�A���{���A�т����Ȃǖ�ܕS�_����

�W�A�W���������������ق�����A�^�C�k�����̃~�����}�[�����n�тɂ��郁�z���\�����N�����A���ɊJ�ق����B

�W�A�W���������������ق�����A�^�C�k�����̃~�����}�[�����n�тɂ��郁�z���\�����N�����A���ɊJ�ق����B

�@�풆����s�풼��ɂ����āA���{�����n���̐l�X�ɔ������������������i���A���Ȃ葽���̉ƒ�Ɏ��������

����̂�m�����N�����A���x�@���̃`���[�`���C�����炪�Z���ɋ��͂����߂��Ƃ���A��\�l���W���ɓ��ӂ����B�J

�َ��ɂ̓p�N�e�B�m���A�����w���A��ʏZ�����Z�S�l���o�Ȃ����B�����{�R�ɂ�����锎���ق͑זɁi�����߂�j

�S���Œm����^�C�����J���`���i�u���ɂ����邪�A���{�R�̕�����i������قLj�J���ɏW�߂��̂̓^�C�ł͏�

�߂āB

����̂�m�����N�����A���x�@���̃`���[�`���C�����炪�Z���ɋ��͂����߂��Ƃ���A��\�l���W���ɓ��ӂ����B�J

�َ��ɂ̓p�N�e�B�m���A�����w���A��ʏZ�����Z�S�l���o�Ȃ����B�����{�R�ɂ�����锎���ق͑זɁi�����߂�j

�S���Œm����^�C�����J���`���i�u���ɂ����邪�A���{�R�̕�����i������قLj�J���ɏW�߂��̂̓^�C�ł͏�

�߂āB

�@�����ق��J�������@�ɂ��Ēm���́u���{�R�̎c�s���Ɏ���u���J���`���i�u���i�̔����فj�Ƃ͈Ⴄ�B�^�C�l���ꂵ

�߂�ꂽ���A���{�������Ƃ̖��߂ł����܂ŘA��Ă����ċ�ɂ𖡂�����B�푈�̔ߎS�����e�[�}���v�ƌ����Ă���B

�߂�ꂽ���A���{�������Ƃ̖��߂ł����܂ŘA��Ă����ċ�ɂ𖡂�����B�푈�̔ߎS�����e�[�}���v�ƌ����Ă���B

FOR THE PUROPOSE CONSTRUCTION OF THE MEMORIAL A JAPANESE WARRIOR REMAINS IN WORLD WAR

�U AT BAN HUAY PONG AND 61 STUDENT'S SCHOLASHIPS AT WAT MOY TOR, KHUN YUAM DISTRICT:

MAEHONGSON THAILAND SEPTEMBER 22; 2000.

�U AT BAN HUAY PONG AND 61 STUDENT'S SCHOLASHIPS AT WAT MOY TOR, KHUN YUAM DISTRICT:

MAEHONGSON THAILAND SEPTEMBER 22; 2000.

HAVING PARTICIPATION TO BRING REMAINS OF JAPANESE WARRIOR IN WORLD WAR �U BACK HOME AND

TO BRING BACK THE PEACEFUL MIND TO THEM AND THEIR RELATIVES ARE ALSO GREAT HAPPINESS WE

PRIDE.

TO BRING BACK THE PEACEFUL MIND TO THEM AND THEIR RELATIVES ARE ALSO GREAT HAPPINESS WE

PRIDE.

Pol.lt.Col. CHIEDCHAI CHOMTAWAT

DECEMBER 17, 2000

|

�b�h�`�m�f�l�`�h�@�l�`�h�k�� �i�݃`�F���}�C�j �`�t�f�t�r�s�@30, 2003�̋L�� Japanese soldiers remembered during WW �U commemoration day held last week in Chiang Mai |

Nnttanee Thaveephol

�@Since World War�Uended in 1945, nobody can deny that the lost and tears were left in any part of the world. Even

a country like Thailand, which should not have been involved, was also forced to participate in the war, creating war

stories that are recounted up to the present day.

a country like Thailand, which should not have been involved, was also forced to participate in the war, creating war

stories that are recounted up to the present day.

On August 15, 1945, the Japanese Emperor declared the end of the war and admitted that Japan was defeated

after the country had sacrificed many soldiers. During wartime, Thailand was used as a military base for Japanese

forces and Chiang Mai was one of the soldiers' residences.

after the country had sacrificed many soldiers. During wartime, Thailand was used as a military base for Japanese

forces and Chiang Mai was one of the soldiers' residences.

On the occasion of the 58th anniversary of the end of World War�U, a commemoration day was organized here in

Chiang Mai. Japanese businessmen, non-government organizations' representatives, companions, and some Thai

residents made merit for Japanese soldiers who died in the province and northern region areas during World War�U.

Chiang Mai. Japanese businessmen, non-government organizations' representatives, companions, and some Thai

residents made merit for Japanese soldiers who died in the province and northern region areas during World War�U.

The ritual took place at Wat Muen San, Wua Lai Rd, Tambon Hai Ya, Muang District, Chiang Mai on August 15.

A historian narrated that Wat Muen Sarn was once a residence and field hospital for the soldiers. The place once

contained many injured and dead. The area behind the wat also housed a Japanese banknote printing office, so a

variety of Japanese banknotes were found and put on display as a part of the ceremony exhibition.

contained many injured and dead. The area behind the wat also housed a Japanese banknote printing office, so a

variety of Japanese banknotes were found and put on display as a part of the ceremony exhibition.

Pol. Lt. Col. Chertchai Chomthawat, a former deputy superintendent at Khun Yuam Police Station, Mae Hong Son,

the person who established the World War�U museum in Khun Yuam District, also organized a seminar to recount

events that happened during World War �U.

the person who established the World War�U museum in Khun Yuam District, also organized a seminar to recount

events that happened during World War �U.

Dr. Masanow Umebayasi, a famous Japanese NGO, said that this ceremony was an occasion for Japanese people

living in northern Thailand to gather and recall the incidents that took place in wartime. Many Japanese soldiers

performed their duties in Northern provinces such as Tak, Lampang, Lamphun, Chiang Mai, and Mae Hong Son.

living in northern Thailand to gather and recall the incidents that took place in wartime. Many Japanese soldiers

performed their duties in Northern provinces such as Tak, Lampang, Lamphun, Chiang Mai, and Mae Hong Son.

"Many Japanese soldiers died or vanished in the area. (Officials) have been scouting for the rest who are still

alive, and have found some soldiers living. The ones who passed away left some of their belongings with Thai people,

which have ended up in collections; therefore, we regard those things as evidence to hold a merit making ritual in

order to devote merit for the soldiers' souls every year," remarked Dr. Masanow.

alive, and have found some soldiers living. The ones who passed away left some of their belongings with Thai people,

which have ended up in collections; therefore, we regard those things as evidence to hold a merit making ritual in

order to devote merit for the soldiers' souls every year," remarked Dr. Masanow.

The ritual was held in both Japanese and Thai style. The participants could see the belongings the soldiers left,

such as metal water bottles, clothes, banknotes, and even the letter the Japanese government sent to order Thai

people to follow its regulations during the war.

such as metal water bottles, clothes, banknotes, and even the letter the Japanese government sent to order Thai

people to follow its regulations during the war.

During the ceremony, it was evident to everyone who participated that there is no longer a feud or enmity among

Thai and Japanese people, although the Thais were once forced by the unfamiliar military army and had lost their

independence beneath the fatal battle. On the contrary, the two nationalities pray together for peace, so that

never again will any teardrops be brought to anyone's heart after this nightmare has ended.

Thai and Japanese people, although the Thais were once forced by the unfamiliar military army and had lost their

independence beneath the fatal battle. On the contrary, the two nationalities pray together for peace, so that

never again will any teardrops be brought to anyone's heart after this nightmare has ended.

|

One-Two Chiangmai���i�݃`�F���}�C�j 25/November/2003 Vol.1 NO.18�@�̋L�� |

�\�푈�����ّO�̍L��ɂ́A������ɐ펞���̃W�[�v�����䂩�u���Ă���A�J���炵�ɎK�т��܂܂ɂȂ��Ă���B��

�̂܂܂ł͂��������̋M�d�ȏ؋��i���A������{���{���ɂȂ��Ă��܂��̂ł́H�Ƃ�����ƐS�z�ɂȂ��Ă��܂��B������

�̌����O�ɂ͓��̊ۂ��f�����A��F�ɂ���Č��Ă�ꂽ�ԗ쓃������B�ٓ��ɓ���ƁA�܂����̏����i�̐��Ǝ��

�̑����ɋ����B�e�A�R���A�R���A�F���[�A�����A��A���ˊ�A���u���V�E�E�E�悭�������܂ŏW�߂����̂��Ɗ��S�������

���B1995�N�ɂ��̌������ł����Ƃ��A�����͋��y�فA�n���̕����Z���^�[�̂悤�Ȃ��̂ɂ���v�悾�����Ƃ����B�S��

���瑊�k���������̃N�����A���x�@�����`���[�`���C�E�`�����^���b�g���́A���{�R�W�̂��̂�W�����Ă͂ǂ�

���H�ƕʂ̃A�C�f�A���o�����B�푈���A���ɂ�a�@��ݒu���������ȂǂɎ��e������Ȃ��������{���𔑂߂����l��

�Ƃɂ͈�i����������c���Ă��āA�`���[�`���C���͂������j�I�ɋM�d�Ȃ��̂��Ɗ����Ă������炾�B���̒�Ă���

���āA1996�N�ɐ푈�����ق��I�[�v�������B�Ăт����ɉ����đ��l����������Ă�����i�ƁA�`���[�`���C����������

���̑��֏o�����Ď�������čw�������R���N�V�����������āA���݂ł͂��̏��������W�_����1000�_�ɂ��̂ڂ��

�����B�\

�̂܂܂ł͂��������̋M�d�ȏ؋��i���A������{���{���ɂȂ��Ă��܂��̂ł́H�Ƃ�����ƐS�z�ɂȂ��Ă��܂��B������

�̌����O�ɂ͓��̊ۂ��f�����A��F�ɂ���Č��Ă�ꂽ�ԗ쓃������B�ٓ��ɓ���ƁA�܂����̏����i�̐��Ǝ��

�̑����ɋ����B�e�A�R���A�R���A�F���[�A�����A��A���ˊ�A���u���V�E�E�E�悭�������܂ŏW�߂����̂��Ɗ��S�������

���B1995�N�ɂ��̌������ł����Ƃ��A�����͋��y�فA�n���̕����Z���^�[�̂悤�Ȃ��̂ɂ���v�悾�����Ƃ����B�S��

���瑊�k���������̃N�����A���x�@�����`���[�`���C�E�`�����^���b�g���́A���{�R�W�̂��̂�W�����Ă͂ǂ�

���H�ƕʂ̃A�C�f�A���o�����B�푈���A���ɂ�a�@��ݒu���������ȂǂɎ��e������Ȃ��������{���𔑂߂����l��

�Ƃɂ͈�i����������c���Ă��āA�`���[�`���C���͂������j�I�ɋM�d�Ȃ��̂��Ɗ����Ă������炾�B���̒�Ă���

���āA1996�N�ɐ푈�����ق��I�[�v�������B�Ăт����ɉ����đ��l����������Ă�����i�ƁA�`���[�`���C����������

���̑��֏o�����Ď�������čw�������R���N�V�����������āA���݂ł͂��̏��������W�_����1000�_�ɂ��̂ڂ��

�����B�\

|

�@�`�F���}�C�E�k���^�C�@�K�C�h

December/2003 NO.16 �̋L��

|

�@�\���́A�N�����A���ɓ��{�R�����Ă����Ƃ����������ؖ��������Ă��̒������n�߂܂����B�������A���O���L���ꂽ�i

����������A�⍜���@��o���ꂽ�肷��̂������肵�Ă��邤���ɁA���{�̈⑰�̑㗝�Ƃ��Ă��̍�Ƃ����Ă���Ƃ���

�C�����ɂȂ��Ă��܂����B���Б����̓��{�l�ɂ��̔����ق����Ă������������B���{�R�́A�A�V�A�̍��X�Ŏc�s�ȍs��

�����Ă������Ƃ���������Ă��܂��B����͂����炭�����ł��傤���A���Ȃ��Ƃ������ł͂���Ȃ��Ƃ͂Ȃ������B�N�����A

���̐l�����͓��{�̕������D���ł����B���̂��Ƃ����̓��{�̐l�����ɒm���Ăق����Ǝv���Ă��܂��B

����������A�⍜���@��o���ꂽ�肷��̂������肵�Ă��邤���ɁA���{�̈⑰�̑㗝�Ƃ��Ă��̍�Ƃ����Ă���Ƃ���

�C�����ɂȂ��Ă��܂����B���Б����̓��{�l�ɂ��̔����ق����Ă������������B���{�R�́A�A�V�A�̍��X�Ŏc�s�ȍs��

�����Ă������Ƃ���������Ă��܂��B����͂����炭�����ł��傤���A���Ȃ��Ƃ������ł͂���Ȃ��Ƃ͂Ȃ������B�N�����A

���̐l�����͓��{�̕������D���ł����B���̂��Ƃ����̓��{�̐l�����ɒm���Ăق����Ǝv���Ă��܂��B

|

���H�C�X���[�����i�݃o���R�N�j 24 MAR 2004 Vol.2 NO.221 �̋L�� |

�@�o���R�N�ɕ�炷���{�l�ɂƂ��āA�~�����}�[�ƍ�����ڂ��郁�[�z���\���͂܂��ɍʼnʂĂ̒n�ɈႢ�Ȃ��B����

���֍s���c�A�[�ɂł��Q�����Ȃ�����A�ő��ɍs���@����Ȃ��̂ł͂Ȃ����H�܂��Ă�[�z���\��������70�j������

�Ƃ���ɂ���c�ɒ��N�����A���܂ő����̂��l�͏��Ȃ��B����11�`12�����Ɍ����ẮA���̂������̋u��ʂɍ炫��

���h�[�N�E�u�A�g�[���i�T���t�����[�j�߂ɁA��������̌����l���K���B����Ȃ̂ǂ��ŕ��a�Ȍ��i���L���邱��

�y�n�ɁA���ē��{�R���吨����Ă��Ě삵�����̎Ⴂ���m���S���Ȃ������Ƃ��ǂꂾ���̐l���m���Ă���̂��낤

���H

���֍s���c�A�[�ɂł��Q�����Ȃ�����A�ő��ɍs���@����Ȃ��̂ł͂Ȃ����H�܂��Ă�[�z���\��������70�j������

�Ƃ���ɂ���c�ɒ��N�����A���܂ő����̂��l�͏��Ȃ��B����11�`12�����Ɍ����ẮA���̂������̋u��ʂɍ炫��

���h�[�N�E�u�A�g�[���i�T���t�����[�j�߂ɁA��������̌����l���K���B����Ȃ̂ǂ��ŕ��a�Ȍ��i���L���邱��

�y�n�ɁA���ē��{�R���吨����Ă��Ě삵�����̎Ⴂ���m���S���Ȃ������Ƃ��ǂꂾ���̐l���m���Ă���̂��낤

���H

�@�N�����A���̃r���}�l���̂������b�g�E���A�C�g�[�O�ɓ��^�C�����̍������f����ꂽ�����{�R�푈�����ق�����B

����܂ň�ʂɂ͂قƂ�ǒm���Ă��Ȃ���������E���̃��[�z���\���Ɠ��{�R�̊W�A���j�I�������

���X�̋M�d�ȕ��i���W������Ă���B�Ȃ����̃N�����A���Ɏ��ʂƂ��ɂ��ꂾ���̂��̂��̂�����Ă����̂��낤���H

����܂ň�ʂɂ͂قƂ�ǒm���Ă��Ȃ���������E���̃��[�z���\���Ɠ��{�R�̊W�A���j�I�������

���X�̋M�d�ȕ��i���W������Ă���B�Ȃ����̃N�����A���Ɏ��ʂƂ��ɂ��ꂾ���̂��̂��̂�����Ă����̂��낤���H

POL.LT.COL.CHIEDCHAI CHOMTAWAT �\�����O�������ĉ������B �u�`���[�`���C�E�`�����^���b�g�ł��B�v �\���N�͉��ł����B �u62�ɂȂ�܂��B�v �\���X�̓N�����A���̌x�@�����������Ǝf���Ă��܂����A �x�@�����ɂ͂�����A�C���ꂽ�̂ł��傤���B �u1995�N�Ɍx�@�����ɕ��C���܂����B�����āA ��N��60�܂ł�����ŋΖ����Ă��܂����B�v |

�\�J�ق���7�N�ȏ�ɂȂ�Ƃ̂��Ƃł����A �����悻�N�ԉ��l���炢���ق��Ă���̂ł����H �u�����ł��ˁA�ŋ߂ł͂����悻�A4�`5,000�l���x�̕��������Ă��܂��B�v �\���{�l�͂��܂藈�Ă��Ȃ��̂ł����H �u����ȂɁA�����͂���܂��A���܂ɗ��ق��Ă���悤�ł���B�S�̂̂T���Ƃ����Ƃ���ł��傤���H�v �\�����ق̎����͔N�Ԃǂ̒��x����܂����H �u��20,000�o�[�c�̃h�l�[�V�������āA����ŁA�N�Ԃ̌o���d���Ă���̂ł��B�v �\����͔����ق��ǂ̂悤�ɂ��ꂽ���ƍl���Ă����܂����H �u�������܂ł����̎d�����o�����ł͂���܂���̂ŁA���������W�߂������U�킵�Ȃ��l�ɔ����ق��N�����A���̌S�̐l�𒆐S�ɍ��c�@�l���������Ǝv���Ă��܂��B�o���R�N����͉����͂���܂����A�݃^�C���{�l�̕��͈�x�͑����^��ł��������B�����ď\���ȓW���i�ł͂���܂��A�̑����̓��M�̕��������������l���Ă��������B�v |

�@���̖�����E���̐��N�O�Ƀ`�F���}�C�ŐA����ꂽ���Ƃ�����B�A�����̂́A�i�����b�g���̋߂��A�`�F���}

�C�N���X�`�����w�Z�̋߂��Ɏʐ^�فu�^�i�J�v���J���Ă����A�l.�c���ł���B���̎ʐ^�ق͘r�̗ǂ����ƂŒm���Ă�

���B����E��킪�N����ƁA�c���͓��{�R�̗��R�����ƂȂ����B��O���牽�N���`�F���}�C����p�[���ɂ�����

�Ƃ����̗��R�ł���B�c���͎����̎ʐ^�ق̑O�A�s���͂̊ݕӂɉ����č���A�����B�c���̓`�F���}�C�̗L�͎ҁA��

���҂̑����ƒm�荇���������B���̂Ȃ��ɁA��������̐l�̑��h���W�߂Ă���A�N���[�o�[�V�[�E�B�`���C�������B�N���[

�o�[�V�[�E�B�`���C�͐l�X�Ɨ͂����킹�ăX�e�[�v�R�ɂ��鎛�@�ƕ����֓o��Q�����J�����l���ł���B�c���́A����

�X�e�[�v�R�ɂ�����A�����B

�@1943�N�͂��߁A�������l���R�������^�C���ł̎i�ߊ��ƂȂ�A�^�C�����̊����͂��ׂĔނ��Ƃ肵���邱�ƂƂȂ����B

�������A�S���̎{�݂����́A��ԋǂ̎i�ߊ������d�����B�������R�����́A�k���^�C�n������@�����Ƃ��A�X�e�[

�v�R�ɂ��Q�q���A�c�����A���������ӏ܂����B1943�N4��2���̂��̓��A���͖��J�������B

�@�c�����A�������́A���{�l�ƃ^�C�l�̗F�D�̂��邵�Ƃ��ď��߂ĐA����ꂽ���̂������B�h�C�X�e�[�v��̍��ƌĂ�

��A������d�̉Ԃ��炩������ŁA�ǂ�ǂ����B�܂��A���̍��̖̔���Ϗo������A�����ɒЂ����肵�āA�ɂ�

�~�߂⋭�s�܂Ƃ��Ďg���l�������B��������ނƗ͂��o��̂ŁA��Ղ̉��̖i�g���E�p���[�E�X�A�N�����j�ƌĂ���

���ɂȂ����B�i�����b�g���߂��A�s���͂̊ݕӂɉ����ĐA����ꂽ���́A�`�F���}�C�s�����̐���������ۂɐ�|���Ă�

�܂��A���݂͎c���Ă��Ȃ��B

�ْ��@�`���[�`���C�E�`�����^���b�g

�i����17�N7��1���j

|

�@�ǔ��V�� �@����17�N7��20������ ���ۖ� |

�@���풆�A�C���p�[�����ɔ����ăr���}�i���~�����}�[�j�����ɋ߂��^�C�k���œ��H���݂Ɍg��������{�R��

�m�̌g�ѕi�Ȃǂ��R�c�R�c�Ǝ��W���A�u����E��픎���فv�̊J�قɊ�^�����^�C�l������B�`�F���}�C�ݏZ�̃`��

�[�`���C�E�`�����^���b�g����i63�j�B���60�N���}���A�`���[�`���C����͊W�҂̘V��ƂƂ��ɏ����䂭�L�����Ƃǂ�

�悤�ƁA���{�l�L�u�̋��͂����āA�����وێ��Ȃǂ̂��߁u���E�^�C���a���c�v�ݗ����ڎw���Ă���B

�@1995�N�ɃN�����A���S�x�@�����Ƃ��ĕ��C�����`���[�`���C����́A�e�ƒ�ŁA�����{���̐�����O���A�ѕz�A�S�|

�w�����b�g�Ȃǂ��ۊǂ���Ă��邱�ƂɋC�Â����B

�w�����b�g�Ȃǂ��ۊǂ���Ă��邱�ƂɋC�Â����B

�@��������i�߂�ƁA�����̕i�X�́A�����{�����H�Ƃ�ʕ��ƈ��������ɒn���̃^�C�l�ɗ^�������̂������B��

���A�A�W�A�����ɓ`��鋌���{�R�́u�؍s�v�Ƃ͋t�ɁA���m�ƒn���Z���̊W�͋ɂ߂ėǍD�ŁA�F��͂����܂�Ă�

�����Ƃ��m�����Ƃ����B

���A�A�W�A�����ɓ`��鋌���{�R�́u�؍s�v�Ƃ͋t�ɁA���m�ƒn���Z���̊W�͋ɂ߂ėǍD�ŁA�F��͂����܂�Ă�

�����Ƃ��m�����Ƃ����B

�@�h�q���h�q�������ɂ��ƁA�N�����A���ɒ��Ԃ��Ă����̂́u��j�p���v�ɋL�q�̂������R�w�����̑�21�t�c�H

�����ŁA��i�͓��H�����̂��̂ƌ�����B

�����ŁA��i�͓��H�����̂��̂ƌ�����B

�@�u�����ɓ��{�������āA�^�C�l�ƌ𗬂����������L�^�Ɏc�������v�B�`���[�`���C����́A�Ƃ������S�̌���������

�{�R�̔����قɂ��悤�Ǝv�������A�펞���̏̒�����i�߂���ŁA�����يJ�݂ɐs�́B96�N�A�J�قɂ�������

���B

�{�R�̔����قɂ��悤�Ǝv�������A�펞���̏̒�����i�߂���ŁA�����يJ�݂ɐs�́B96�N�A�J�قɂ�������

���B

�@�W���i��9���́A�`���[�`���C����100���o�[�c(270���~)�̎���𓊂��A�Z�����甃���������A�~�����}�[�̓�

���炳�ѕt�����R�p�ԗ��������肷��Ȃǂ��Ď��W�B�����i�͌��݁A1000�_�ɂ̂ڂ�B

���炳�ѕt�����R�p�ԗ��������肷��Ȃǂ��Ď��W�B�����i�͌��݁A1000�_�ɂ̂ڂ�B

�@���{�R��43�N���납��A�n���̃^�C�l���ٗp���ē��H���݂ɂ����点���B�����A���{�R�ɋ��͂����x�@�����̑��q

�W�����[���E�`���I�v�����[������(70)�́A�u���@��w�Z�ɒ��Ԃ��Ă������{���͋K���������A�q���̖ʓ|��������A��

�������`�����肵�Ă��ꂽ�v�ƐU��Ԃ�B

�W�����[���E�`���I�v�����[������(70)�́A�u���@��w�Z�ɒ��Ԃ��Ă������{���͋K���������A�q���̖ʓ|��������A��

�������`�����肵�Ă��ꂽ�v�ƐU��Ԃ�B

�@�������A44�N�Ɏn�܂������d�ȃC���p�[�����ŏ���ρB�r���}����s���������{���������炪��N�����A����

���ǂ蒅���ƁA�Z���͉�����ĐH�ו���^�����B�r���}�ł́A�s���|�ꂽ���{���̈�̂��U���A�ދp�H�́u�����X���v

�ƌĂꂽ�B�N�����A���ŁA���{�R�����݂������H�́A���̏I���_�Ƃ��Ȃ�A�����̈�̂�����������B

���ǂ蒅���ƁA�Z���͉�����ĐH�ו���^�����B�r���}�ł́A�s���|�ꂽ���{���̈�̂��U���A�ދp�H�́u�����X���v

�ƌĂꂽ�B�N�����A���ŁA���{�R�����݂������H�́A���̏I���_�Ƃ��Ȃ�A�����̈�̂�����������B

�@�����r���}�ŌR�n�̐��b�����Ă����b��t�̈�㒩�`����(83)(�R�����h�{�s)�́A�}�����A�������Ȃ���N�����A��

�̕a�@�ɂ��ǂ����1�l�B�u���̓^�C�l�̂������ŁA�����ē��{�ɖ߂ꂽ�v�ƌ��B

�̕a�@�ɂ��ǂ����1�l�B�u���̓^�C�l�̂������ŁA�����ē��{�ɖ߂ꂽ�v�ƌ��B

�@�`���[�`���C����͍��N3���A�`�F���}�C���ɍ��c�ݗ���\�������B�^�C�ŏ�s����ыς���(43)����{�l�L

�u3�l������Ɏ^���B�����ق̈ێ���Ǘ���A���{���ɂ���������l�����̕n���~�ςȂǂ�ڎw���B

�u3�l������Ɏ^���B�����ق̈ێ���Ǘ���A���{���ɂ���������l�����̕n���~�ςȂǂ�ڎw���B

�@�u���{�����������n���̃^�C�l�͎��X�ƖS���Ȃ��Ă���B���c���班���ł��������Ă��������v�Ɨт���B�`���[�`���C

������u���E�^�C�F�D�̏ے����㐢�ɓ`�������v�Ƙb���Ă���B

������u���E�^�C�F�D�̏ے����㐢�ɓ`�������v�Ƙb���Ă���B

|

|

|

|

�@����17�N8��15���A�`�F���}�C�����A���S�̃��[���T�[�����@�ɂāA����I��60���N���{��������s�Ȃ��

���B�O������̍^���ɂ�����炸�A���{�l�̎Q���Җ�70���A�^�C�l�̎Q���҂���������ꂽ�B

���B�O������̍^���ɂ�����炸�A���{�l�̎Q���Җ�70���A�^�C�l�̎Q���҂���������ꂽ�B

�@

�@���́A���{�̐��߂̎��T�ɍ��킹�āA�^�C���Ԃ̌ߑO10���̖ٓ�����n�܂�A�ԗ��ɐ����������Ă��Q�����

���B���̎�Ȃł���A�W�����[���E�`���I�v�����[���搶���A��펞�̃��[���T�[�����@�̗l�q��A�����̓��{����

�^�C�l�̗F�D�W�Ȃǂɂ��Ă̐����ƈ��A���������B���̌�͒��H��s��ꂽ�B

���B���̎�Ȃł���A�W�����[���E�`���I�v�����[���搶���A��펞�̃��[���T�[�����@�̗l�q��A�����̓��{����

�^�C�l�̗F�D�W�Ȃǂɂ��Ă̐����ƈ��A���������B���̌�͒��H��s��ꂽ�B

�@���̎��@���A���{�l�ƃ^�C�l�ɂƂ��ďd�v�ȈӖ������ꏊ�̂ЂƂ��ƁA�l����悤�ɂȂ��Ăق����ƃ`���[�`���C

�ْ��͌�����B

�ْ��͌�����B

| �V���̂��ē� |

|

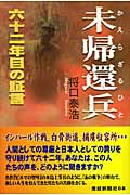

���A�ҕ��i�����炴��ЂƁj �Z�\��N�ڂ̏،� �����_�@Shoguti Yasuhiro �����Q�O�N�P���Q�Q������ �l�Z���E�㐻 �Q�P�Q�y�[�W �{�̂P�C�T�O�O�~�i�ō��P�C�T�V�T�~�j ISBN978-4-86306-044-9 ���s���@�Y�o�V���o�� |

�@

�@���̐푈�B���d�Ƃ��v�����u�C���p�[�����v�̎��s�ɂ���āA�����̒��Ԃ������A

��������g�n�w�ƂȂ��āA�h�����X���h���悤�ɂ��ǂ�A�㎀�Ɉꐶ���j�����B

�@�H�ׂ���̂��A������̂��Ȃ��A�����Ă�����Ȃ������B�������A�ނ�͐����̂т��B

�����āA�l�ԂƂ��Ă̑����ƁA���{�l�Ƃ��Ă̌ւ����葱�����B

�@�������A�ނ�͑c���E���{�ɋA��Ȃ������B

�u�ǂ����āA�A�҂��Ȃ������̂ł����H�v�ƒ��҂͖₤�B

�Ȃ��ނ�͋A��Ȃ������̂��H

�@�ނ���{�����r���}�i�~�����}�[�j��^�C�̐l�����́A�D�����}�����ꂽ���ꂽ�B

�|�R���Y�̖���u�r���}�̒G�Ձv�̐����㓙���̂悤�ɁA�����{�ɋA�炸�A���̒n��

�V���Ȑl�����J���Ă������j�����̔߂����܂ł̋ꓬ�B

�@���ꂼ��́u�A�炴�闝�R�v�����Ȃ��́A�ǂ������܂����H

�l�ԂƂ��Ă̑����ƁA���{�l�Ƃ��Ă̌ւ����葱�����Z�\��N

���e

�C���p�[�����

�v�����[�O���픎����

��P�́@�A��Ȃ������O�l�̓��{��

��Q�́@�ЂƂ�ۂ����̋e����

��R�́@�E���y�ƌĂꂽ�j

��S�́@���{���̈�i

��T�́@���{�l�̌�

|

|

H22�N2���A�`���[�`���C���͉����`���N���[�V�����g�[���l�ފw�Z���^�[�́AWW2�ł̃^�C�k�����{�R�̒��������̗v

�����ċ��͂����B

�����ċ��͂����B

�@

�@